Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (8 page)

If he were planning to return, the driver had not only to keep all these tickets, but to find the right one to present at each gate in turn. In

Oliver Twist

, when Noah Claypole is disguised as a waggoner by Fagin, in addition to the usual smock and the leggings, he is given ‘a felt hat well garnished with turnpike tickets’ for that final touch of verisimilitude.

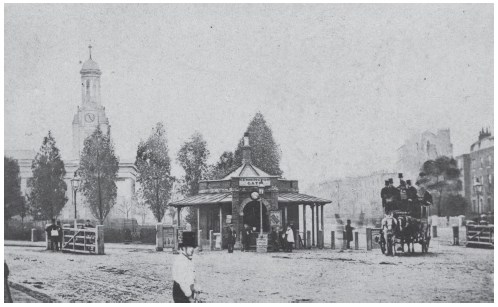

Toll gates therefore constricted trade as well as slowing down traffic, and in 1829 an Act was passed to transfer the costs of upkeep from the turnpike trusts to the local parishes. On 1 January 1830, a few (very few) turnpikes were abolished: Oxford Street, Edgware Road, the New Road, Old Street and Gray’s Inn Lane all became toll free. By the 1850s, there was one toll gate left in Westminster and none in the City. But most of the surrounding

areas, and the roads leading into and out of London, kept theirs: there were 178 toll bars charging between 1d and 2s 6d in the surrounding suburbs and on the bridges. This cost had to be taken into account by traders, individual sellers and big companies alike, and had to be included even in the cost of a night’s entertainment. One of the reasons Vauxhall pleasure gardens declined in popularity was the expense: not just the 2s 6d for admission, nor even the price of a cab to get there, but the cost of ‘the bridge-toll and a turnpike – together ninepence’. Yet the campaign to abolish all the turnpikes had still not achieved its goal. A deputation of MPs noted tartly that a Select Committee had recommended that the number of gates be reduced; instead it had increased, from 70 to 117 around London. ‘(Laughter.)’ The prime minister, Palmerston, as is the way of all politicians, ordered another inquiry. In 1857, 6,000 people turned out at a ‘Great Open-air Demonstration’ to object to the toll that was being imposed on the bridge about to open between Chelsea and Battersea. The toll, they protested, would prevent the working classes having free access to Battersea Park – a park that had recently been created at public expense precisely to provide a recreation space for the people who were suddenly being priced out of it. The

government ministers whipped into action: they set up another committee. It was not until 1864 that the last eighty-one toll gates within fifty miles of London on the Middlesex (northern) side of the river were abolished.

Four months later, Southwark Bridge, underwritten by the City of London, began an experiment in going toll free. This was the bridge that in

Little Dorrit

is called the ‘Iron Bridge’. Little Dorrit prefers it to London Bridge, precisely because the penny toll ensures that it is quieter, while Arthur Clennam uses it when he finds ‘The crowd in the street jostling the crowd in his mind’. Dickens had a fondness for the old toll bridges: when night walking, he liked to go to Waterloo Bridge ‘to have a halfpenny worth of excuse for saying “Good-night” to the toll-keeper…his brisk wakefulness was excellent company when he rattled the change of halfpence down upon that metal table of his, like a man who defied the night’.

The toll gates were a major traffic obstacle, but not the only one. For much of the century there were, legally, no rules for traffic in most streets. In the 1840s, buses were equipped with two straps that ran along the roof and ended in two rings hooked to the driver’s arms. When passengers wanted to get down on the left side of the road, they pulled the left strap, for the right, the right strap, and the buses veered across the roads to stop as requested. Some streets had informal traffic arrangements. The newsagents, booksellers and publishers who comprised most of the shopkeepers in Paternoster Row mailed out their new magazines and books on a set day each month – ‘Magazine Day’ – and on that day, ‘the carts and vehicles…enter the Row from the western end, and draw up with horses’ heads towards Cheapside’. Even there, from time to time a carter ‘hired for the single job, and ignorant of the etiquette…will obstinately persist in crushing his way on the contrary direction’. It was ‘etiquette’, not law, that made Paternoster Row into a one-way system one day a month. In 1852, the police first issued a notice that, because of severe traffic problems at Marble Arch, on the northeast side of Hyde Park, ‘Metropolitan stage-carriages are to keep to the left, or proper side, according to the direction in which they are going, and must set down their company on that side. No metropolitan stage-carriage, can be allowed to cross the street or road to take up or set down passengers.’ The word ‘proper’ still suggested etiquette, but the involvement of the police

was new: the press carried furious debates on this intrusion into what had up to now been an entirely private matter.

As late as 1860, traffic was still segregated in a variety of ways, different for each road, with no overarching rules. When the new Westminster Bridge opened in 1860, ‘Light vehicles are to cross the bridge each way, on the western side; omnibuses, waggons, &., on the two tramways, on the eastern side’, while the old bridge was reserved for ‘foot-passengers, saddle horses, trucks [hand-carts], &c’. There was still no separation for traffic moving in opposite directions. (It is interesting to see that riding horses were categorized with pedestrians, not with wheeled vehicles.) In 1868, a lamp was erected near Parliament Square that ‘will usually present to view a green light, which will serve to foot passengers by way of caution, and at the same time remind drivers of vehicles and equestrians that they ought at this point to slacken their speed’: a proto-traffic light. (It exploded and wounded a policeman, which put an end to that experiment for the time being; a plaque marks the spot.) The following year the police first took on the duty of directing traffic, even though the public continued to query whether they had the legal authority to enforce drivers to act in certain ways. The author of an 1871 treatise on how to improve traffic referred to the ‘rule of the road’, where vehicles were expected to stay ‘as close to the “

near

side” as possible’, but then went on to say that no one actually complied: traffic converged naturally on the best part of the road, the central line. In some countries, he added, it was part of the duty of the police ‘to chastise any driver they might see transgressing, or fine him’, but in England there would be ‘objections...against such power being given to the police’.

The nature of horse transport meant that some slowdowns were inevitable. The logistics of horses and carts required endless patience. Even important streets, such as Bucklersbury in the City, were too narrow for many carts to be able to turn, and their horses had to back out after making deliveries. Railway vans, transporting goods to and from stations, weighed two tons, their loads another thirteen; brewers’ vans carried twenty-five barrels of beer weighing a total of five tons; the carts that watered the streets held tanks of water weighing just under two tons. Manoeuvring these great weights, and the large teams of horses needed to pull them, required time as well

as skill, as did the ability to handle a number of animals. Brewers habitually used three enormous dray horses harnessed abreast, while other carters with heavy loads might use six harnessed in line one in front of the other. Extraordinary events required even more: in 1842, the granite for Nelson’s Column was shipped by water to Westminster and was then transported up to Trafalgar Square in a van pulled by twenty-two horses. Even when not conveying these vast loads, drivers of heavily laden carts often needed to harness an extra horse to deal with London’s many hills. Some bus and haulage companies kept additional horses at notoriously steep spots, such as Ludgate Hill, the precipitous side of the Fleet Valley. But otherwise individuals went to the aid of their fellow drivers on an ad hoc basis. A carter seeing another carter in difficulty would stop, unharness one or two of his horses and lend them to the passing stranger, who yoked up the animals to his cart, then stopped at the top of the hill to unharness them and return them to their owner, who was presumably blocking traffic while he waited. Tolls and turnpikes caused more delays – particularly where goods for sale were brought into the city, as their tolls were calculated by weight, and carts had to stop at each weighing machine.

Road layouts were also a major cause of delays, especially as the roads themselves were narrow. Temple Bar, that divider between the West End and the City, was just over twenty feet across, while almost all carriages were more than six feet wide, and carts often much more. In other streets, centuries of building accretions did not help. Until the early 1840s, the Half-way House stood in the middle of Kensington Road, the main route into London from the west, narrowing it to two alleys on either side, while Middle Row in Holborn was just that: a double-row sixty yards long of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century houses occupying the middle of the street. (Dr Johnson was said to have lodged there briefly in 1748.) This row of shops, lawyers’ offices and pubs narrowed one of London’s busiest roads at the junction of Gray’s Inn Lane (now Gray’s Inn Road) to just ten yards. The caption to an 1820s engraving of Holborn at Middle Row reads, ‘The part here exhibited is perhaps the widest and best of the whole line of street.’ One can imagine what the rest of it looked like. Middle Row was demolished only in 1867, widening the street to nearly twenty-five yards.

The main problem for traffic, however, was a historic one. London had developed on an east–west axis, following the river, with just three main routes: one that ran from Pall Mall via the Strand and Fleet Street to St Paul’s; one from Oxford Street along High Holborn; and the New Road (now the Euston Road). Yet none ran clear and straight. Along the Holborn route, the slum of St Giles necessitated a detour before New Oxford Street was opened at the end of the 1840s. A few hundred yards further on lay the obstacle of Middle Row, and 500 yards beyond that was the bottleneck of the Fleet Valley, whose steep slopes slowed traffic until Holborn Viaduct was built across it in 1869. The Strand had its own problems: the western end, until Trafalgar Square was developed in the 1830s, was a maze of small courts and lanes, while at its eastern end Temple Bar slowed traffic to a crawl, as did the street narrowing at Ludgate Hill. It must be remembered that these were the good, wide, east–west routes. North–south routes could not be described as bad, because they didn’t exist. Regent Street opened in sections from 1820, and the development known as the West Strand Improvements began to widen St Martin’s Lane and clear a north–south route at what would become Trafalgar Square. But otherwise there was no Charing Cross Road nor Shaftesbury Avenue (both of which had to wait until the end of the century); there was no single route through Bloomsbury, as the private estate of the Duke of Bedford was still being developed; there was no Kingsway (which was built in the twentieth century); and what is today the Aldwych was until the twentieth century a warren of medieval lanes, many housing a thriving pornography industry.

Plans for improvements were made. And remade. And then remade again. The Fleet market was cleared away in 1826 to prepare the ground for what would ultimately become the Farringdon Road; the Fleet prison too was pulled down; but still nothing happened. A decade later only one section, from Ludgate Circus to Holborn Viaduct, had been constructed. Similarly, in 1864 the

Illustrated London News

mourned that, after decades of complaints, narrow little Park Lane still had not been widened: ‘The discovery of a practicable north-west passage from Piccadilly to Paddington is an object quite as important as that north-west passage from Baffin’s Bay to Behring’s [sic] Strait...The painful strangulation of metropolitan

traffic in the small neck of this unhappy street...is one of the most absurd sights that a Londoner can show to his country cousins.’

25

Even the river blocked the north–south routes: the tolls on Southwark and Waterloo Bridges ensured that the three toll-free bridges – London, Blackfriars and Westminster – were permanently blocked by traffic.

Almost any state or society occasion caused gridlock. As early as the 1820s, when the king held a drawing room – a regular event at which he received the upper classes in a quasi-social setting – carriages were routinely stuck in a solid line from Cavendish Square north of Oxford Street, all the way down St James’s to Buckingham Palace, a mile and a half away. ‘The scene was amusing enough’ to one passer-by, looking in at the open carriage windows and discovering that the elaborately dressed courtiers were ‘devouring biscuits’, having come prepared for what was then known as a ‘traffic-lock’ of several hours’ duration.

Everyday traffic was every bit as bad. One tourist reported a lock made up of a number of display advertising vehicles (see pp. 246–7), a bus, hackney coaches, donkey carts, and a cat’s-meat man (who sold horsemeat for household pets from a handcart), whose dogs got caught up in the chaos. All was in an uproar until a policeman came along, who ‘very quietly took the pony by the head, and drew pony, gig, and gentleman high and dry upon the side-walk. He then caused our omnibus to advance to the left, and made room for a clamorous drayman to pass’, who did so with a glare at the bus and a shake of his whip. Dickens was dubious about such actions, maintaining that policemen rarely did anything except add to the confusion, ‘rush[ing] about, and seiz[ing] hold of horses’ bridles, and back[ing] them into shop-windows’.